A Short Exposition of the Popper-Miller Theorem

Introduction

Probability theory generalizes propositional logic to reasoning with degrees of certainty and has therefore been used as the foundation of the scientific language in which humanity’s best theories of nature are expressed. Science has often been mis-understood to be driven by the process of induction – of obtaining supposedly absolute and general laws from limited observations of nature. Thus, under this assumption, it is natural to expect probabilistic logic to be able to explain the phenomenon of induction. Popper and Miller’s result shatters this expectation. This short article attempts to be an intuitive exposition of the Popper-Miller Theorem (Popper and Miller, Letters to Nature 1985).

Central to this topic is the philosophical Problem of Induction first formulated by David Hume. (Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, 1739). The Problem of Induction may be stated as follows:

Given a set of local observations (local in time, space, etc.), how does it logically produce (or rather “induce”) a general theory whose reach goes well beyond the local scope of this data?

Notation

- $h$: proposition representing the general hypothesis

- $e$: proposition representing the local empirical evidence in favor of $h$

The Given

- $e$ is deducible from $h$, i.e. $p(e\mid h) = 1$

- Bayes rule: $p(h\mid e) = \frac{p(h) p(e\mid h)}{p(e)}$

- Assume $0 < p(e) < 1$ and $p(h) > 0$

- Hence: $p(h\mid e) > p(h)$ (Eq.1)

- That is, the probability of $h$ increases in the light of $e$.

- This may lead to the mistaken interpretation that $h$ is induced from $e$ by the process of Bayesian probabilistic inference.

The Problem Formulation

- Popper’s decomposition: $h = (e \lor h) (e \rightarrow h) = d n$

- where $d = (e \lor h)$ is the component of $h$ deducible from $e$, and $n=(e \rightarrow h)$ is the non-deducible component.

- In other words, $h$ is true if $e$ is true AND $h$ holds beyond the scope of $e$.

- Now:

- Without knowing $e$: $p(h) = p(n) p(d)$

- In the light of $e$: $p(h\mid e) = p(n\mid e) p(d\mid e) = p(n\mid e) \cdot 1$

- $p(h\mid e)$ is greater than $p(h)$ (from Eq.1) and $p(d\mid e)=1$ is greater than $p(d)$. But, it’s not clear whether the probability of $n$ increases in the light of $e$.

- Since $n$ goes beyond the scope of the evidence $e$, the problem of induction can be formulated as follows:

- Is $p(n\mid e) > p(n)$?

A Visual Proof

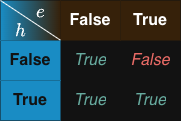

Truth value of $n=e \rightarrow h$ as a function of $e$ and $h$ is shown in the following table:

Note that:

- With no knowledge of $e$, proposition $n$ holds in 3 out of 4 possibilities. In the light of $e$, it holds only in 1 out of 2 possibilities.

- Thus, the more likely $e$ is to be

True, the less likely $n$ is to beTrue.

More concretely:

-

Since $p(n) = p(e,h)p(n\mid e,h) + p(-e,h)p(n\mid -e,h) + p(-e,-h)p(n\mid -e,-h)$

$= p(e)p(h\mid e)\cdot 1 + p(-e,h)\cdot 1 + p(-e,-h)\cdot 1$

$= p(e)p(h\mid e) + p(-e)$,

- And $p(n\mid e) = p(h)p(n\mid e,h) = p(h)\cdot 1 = p(h)$,

-

Therefore, $p(n) - p(n\mid e) = p(e)p(h\mid e) + p(-e) - p(h\mid e)$

$= p(-e) - p(h\mid e)(1 - p(e))$

$= p(-e)(1 - p(h\mid e))$

$= p(-e)p(-h\mid e) > 0$.

- Q.E.D.

- Note: Other proofs are possible, for e.g. Popper and Miller’s original proof (Popper and Miller, Letters to Nature 1985).

In other words:

- The probability of the non-deducible component $n$ decreases after observing $e$. The net increase from $p(h)$ to $p(h\mid e)$ via Bayesian inference is because the increase from $p(d)$ to $p(d\mid e)=1$ more than compensates for the drop from $p(n)$ to $p(n\mid e)$.

- The drop from $p(n)$ to $p(n\mid e)$ is proportional to both $p(-e)$ and $p(-h\mid e)$.

Conclusion

- Any evidence supports a hypothesis only deductively, i.e. so far as the general hypothesis explains the local measurement. Beyond the scope of the evidence, nothing can be said about the truth of our hythothesis, except when considering also the surprise towards the source of this evidence and the chance of falsification of our hypothesis despite this evidence. These latter two factors exist, in a sense, on a level above the evidence itself, and they depend on the background knowledge of the enquiring agent, for e.g. its understanding of the limits of its hypothesis and of its experimental setup.

- Thus, there is no such thing as the (logical probabilistic) process of induction of a general theory from local empirical data. Accumulation of positively supporting pieces of local evidence doesn’t automatically justify our confidence in the general truth of our hypothesis.

- And there need not be any such logical justification. Knowledge (i.e. a body of yet-unfalsified hypotheses about some set of problems) can never be certain, infallible, and all-encompassingly general. This is because any piece of data is fundamentally limited: its sampling is guided by and its interpretative meaning resides in the context of the problem-situation and the set of competing conjectures proposed to overcome the problem.